Initial Algebra

Let’s begin with the definition of a mathematical structure ‘algebra’.

Definition. (algebra) We call a set together with distinguished constants and operations as an algebra.

Example. $(\mathbb{Z}, 0, +, -)$, $(\mathbb{R}_{>0}, 1, \times, (\cdot)^{-1})$ are algebras.

If algebra is given, we can define ‘type’ of that algebra, which is called as a signature. In Java, you can think signature as interface, and algebra as class. We can also define the signature for integer expressions.

Definition. (signature) Signature is a type of an algebra.

Example. $(t, id: t, \circ: t \times t \to t, (\circ)^{-1}: t \to t)$ is signature for $(\mathbb{Z}, 0, +, -)$, $(\mathbb{R}_{>0}, 1, \times, (\cdot)^{-1})$.

Moreover, we may regard a programming language as an algebra! Given grammar, the set of the language expressions represent the programming language itself. Suppose we have following abstract grammar for integer expressions:

\[\begin{aligned} \langle \text{intexp} \rangle ::= &0 \vert 1 \vert 2 \vert \cdots \vert \\ & \langle\text{var} \rangle \vert - \langle \text{intexp} \rangle | \langle \text{intexp} \rangle \oplus \langle\text{intexp} \rangle, \; \oplus \in \{+, -, \times, \div \} \end{aligned}\]The signature for the integer expression algebra is,

\[\begin{aligned} S_{\text{intexp}} = (&t, 0 \in t, 1 \in t, \cdots, \\ & x \in t, y \in t , \cdots, -: t \to t, \oplus : t \times t \to t \text{ where } \oplus \in \{+, -, \times, \div \}) \end{aligned}\]In this way, we can derive a signautre if an algebra is given.

Question. How many algebras would satisfy the signature $S_{\text{intexp}}$?

There can be many algebra having signature $S_{\text{intexp}}$. For instance, we can define a trivial algebra where the domain is a singleton set $\{0\}$. In this algebra, we cannot distinguish 0, 1, $x$, $y$, $x+y$, … everything is collapsed to 0. The algebra we wanted - the algebra of abstract grammar for the integer expression is expressed below. We can think of the set of ‘trees’ that collects all possible abstract syntax trees of the integer expression.

Indeed, you would have some feeling that $A_{\text{grammar}}$ is the most general algebra having signature $S_{\text{intexp}}$. To address it more formally, we define a mapping from ‘general algebra’ to ‘concrete algebra’.

Definition. (homomorphism) Homomorphism is a map between algebras that preserves constants and operations. For algebra $U_0$ and $U_1,$ $h: U_0 \to U_1$ is a homomorphism if

- $h(c_j ^0) = c_j ^1$ for all $i$. In other words, all the elements in set of $U_0$ has corresponding element in the set of $U_1$

- $f(op_i ^0 (x_1, \cdots, x_k)) = op_i ^1 (f(x_1), \cdots, f(x_k))$ for all $i$. This rule says that the operations is also preserved.

Exercise. (composition of homomorphisms) For given signature $S$, there are algebras $U_0, U_1, U_2$. If $h_0: U_0 \to U_1$ and $h_1: U_1 \to U_2$ are homomorphisms, then $h_1 \circ h_0: U_0 \to U_2$ is also homomorphism.

Keep in mind that homomorphism does not guarantee the existance of inverse homomorphism. Even we have homomorphism $h: U_0 \to U_1$, we may not able to find a homomorphism $h^{-1}: U_1 \to U_0$. If we have such inverse homomorphism, we say that $U_0$ and $U_1$ are isomorphic.

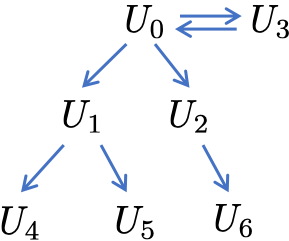

Based on this idea, we can think of a tree-like hierarchy of algebras. Suppose for signature $S$, there are algebras $U_0, U_1, U_2, \cdots$. If we find all the homomorphisms between the algebras, it will be something like:

Then we can imagine that there are roots ($U_0$ and $U_3$) - most ‘general’ algebras of the given signature. We call them as an initial algebra, and this is algebraic foundation of programming language!

Definition. (initial algebra) We say $A$ is an initial algebra of signature $S$ if for all algebras $A^\prime$ of $S$, there exists a unique homomorphism $h: A \to A^\prime$.

Exercise. Prove that $A_{\text{grammar}}$ is an initial algebra of $S_{\text{intexp}}$.

Exercise. If $A_1, A_2$ are initial algebras, then there are homomorphisms $f: A_0 \to A_1$ and $g: A_1 \to A_0$ such that $f \circ g = id$ and $g \circ f = id$. This means that all initial algebras of $S$ are essentially the same, i.e. isomorphic.

Leave a comment